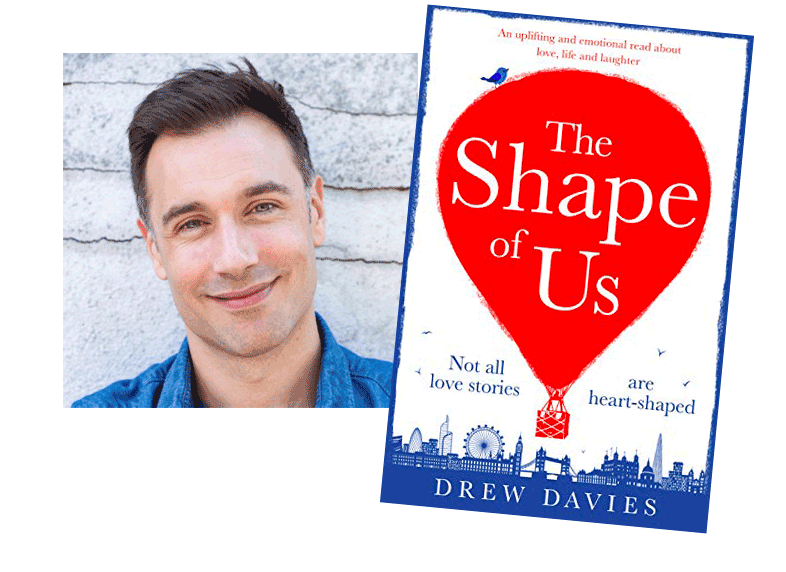

Congratulations to Wanstead author Drew Davies whose first book The Shape of Us is being published today.

Congratulations to Wanstead author Drew Davies whose first book The Shape of Us is being published today.

The Shape of Us is a romantic comedy which has been described as being something like Love Actually and Sliding Doors (though not by Drew). There is an excerpt of the book printed below, but we asked Drew to introduce himself. He writes the following:

It’s a cliché, but I’ve been writing all my life, ha! Short stories and plays as a kid (I directed my first play when I was ten for my primary school assembly). In 2000, I won a New Zealand Playmarket Young Playwright of the Year award, and people started to consider me a “proper” writer. That wouldn’t last. In my twenties, after returning to London, I flailed around, pounding away at a first novel, which never came to fruition, and putting on scrappy off-beat comedies that had glimmers of success (a good review here and there at the Edinburgh Fringe), but were also met with looks of bewilderment. I would like to say I was ahead of my time, but in reality I was deep into my apprenticeship – the hard graft of learning to write. During these years, I also fell into a career as a copywriter and search engine optimiser, telling big brands exactly what to do with their content to make it successful (the irony was not lost on me).

The Shape of Us is my first romantic comedy. I started writing it back in 2012, when I’d just moved into a new flat. I didn’t have internet yet, and there were a few quirky stories floating around my head, so I decided to get them down finally. I finished the first three chapters pretty smartly, and then spent the next few years completing the rest. The book is about love, and life, and living in this great city (my working title was “An Invisible Guide to London”) – warts and all – through the eyes of a disparate group of Londoners: a teenager in Croydon struggling with M.E and a burgeoning romance, a sixty-three year old wife in Battersea trying to win back her adulterous husband, a chap illegally squatting in an investment bank while also trying to woo the receptionist, and two lovers attempting to do the impossible – successfully date in London. Their stories soon start to interweave… Someone recently said it was “a little Love Actually in all the best ways” (full disclosure, I have never actually seen Love Actually).

I moved to Wanstead two and a half years ago, and I love it. I am deeply in love with the place. I love the sense of community, and the high street, and the green spaces. There’s a sense of calm I always feel getting off at Snaresbrook station. I sometimes write at The Currant, and The Starbucks (RIP), and I’m having my book launch at Bare Brew. I regularly use the Wanstead library (mostly for coffee table books with nice undemanding pictures I can get lost in when I’m procrastinating), and I volunteer for Barnardo’s locally. Over the years, I’ve lived in Bethnal Green, Clapham, East Dulwich and Angel, but I feel most settled in Wanstead. I have lots of family in the area too which helps the sense of belonging.

I’m very excited about the book coming out. It’s such a privilege to have anyone read your writing, for someone to spend time contemplating your contemplations. I’m deep into the second book now (which will be out in May 2019) – that’s what is currently keeping me up at night. So if you see me wandering the high street, with bed hair and a far-away look in my eyes, muttering about coffee, hopefully you’ll understand why.

The Shape of Us is out now. You can buy a copy from Amazon here.

Chapter One

‘London,’ they say, eyes twinkling. ‘London is a city for lovers!’

Look down the sweeping avenues of Shaftesbury or Sloane

and you’ll find them, hands entwined, cheeks pink and dimpled

with joy, loving at each other. On the Tube they’ll self-consciously

flirt (though not self-consciously enough, you’ll sniff, ruffling the

Evening Standard). He’ll make a grand gesture of offering her the

empty seat or perhaps she’ll perch coquettishly on his lap – while

the rest of the carriage tries desperately to ignore them.

Yes, London is for the young and in love, but loathed are

they by all good Londoners. Like tourists and pigeons, lovers

are a blight on this great city – a fact they are completely (and

conveniently) blind to. That is, until one day, when a lover finds

themselves standing behind a couple so amorously entwined it’s

a wonder the cheap bottle of Spanish red they’re holding doesn’t

smash to the floor – in fact, they want it to smash – and suddenly

our lover finds themselves under stark fluorescents, unable to wait

for the self-service checkouts after all and quite out of love with

the idea of love. But until then, my friend (twinkle, twinkle),

until then!

*

Here come Chris and Daisy – two soon-to-be lovers – now, both

hurrying towards their meeting point near Embankment station,

both in their early thirties, both thinking they are the only one who

is twelve minutes late for their first date. She is quite lovely – her

hair in brown curls that took two attempts and a navy dress she

‘borrowed’ from work that floats in all the right cleavage-type

places and none of the thigh-revealing wrong ones. He is holding

a copy of The Big Issue that he hopes will make him seem more

edgy and less posh than he is, and is wearing jeans that do good

things for his rather square buttocks. Chris looks younger than

he has a right to and, all things considered, fairly handsome.

A few paces from the meeting point, they finally see each

other and realise they are not the only one late, and oh the relief,

and how funny to arrive at exactly the same moment, and they

take in the smells of each other (him: soap and sandalwood,

her: jasmine and the slight zest of something – deodorant?) and

talk and laugh like this for some time before realising they have

successfully side-stepped the awkward ‘Do I kiss you on one

cheek or two?’ routine and cut straight to ‘Can I hold the cuff

of your jacket while I adjust my shoe?’ Once Daisy’s heel strap

is fastened in place, they walk down the steps to the riverside

entrance to Gordon’s Wine Bar, a popular drinking grotto (and

the capital’s oldest), still chatting breathlessly, until the gloom

and the heat of the cave-like bar stifles them. Why did I suggest

this place? Chris thinks. It’s one of those bars he’s always meaning

to go to, but never does – in his mind it is full of dripping

candles and romantic hideaways – in reality it’s cramped and

dark and full of overbearing men, who are yelling at someone

called Smithee to get three bottles, not two. With a conspiratorial

nod, the couple head back up into the daylight to the long row

of tables and chairs outside the bar instead. It’s busy here too,

though – they nab one seat, which Daisy guards with Chris’s

jacket, while he walks the length of the terrace, seeing if any

more are free. As he hustles the tables, she watches his style:

charming, direct, not too flirty with the ladies, not too ‘alright,

mate?’ with the guys. His first three attempts are thwarted as

the empty seats are being held for people, but he pushes on

and finally returns to her, eyebrows wiggling in victory, with

the prize of another chair.

It is only now, after Chris positions the chair beside Daisy and

sits, that they really look at each other.

He’s less goofy than she remembers, or maybe less goofy

than the mental image of him she’s been turning around in her

mind the past week. Could she kiss him? The answer comes

immediately: Yes. Good. Daisy could do with a drink, though.

She hopes he’s not going to be one of those men who barely

touches his glass, forcing her to sneak sips when he’s not paying

attention. She had six months off the booze last year, mostly just

to prove she could, and yes, her skin was better and she barely

missed a yoga class, but she felt too good, too chaste, and restless,

with so much extra time. When she caught herself ironing

bed sheets one Saturday morning, she knew it was either start

drinking again or join a nunnery.

Chris decides Daisy looks different too, better. What is it? She’s

softer around the eyes than when they first met. This is probably

not surprising considering he cycled up to her from nowhere and

brazenly asked her out. He wasn’t usually so impulsive, but the Boris

bike he’d rented had given him such a wonderful sense of freedom,

whizzing around the West End with the spokes humming, that he’d

felt intoxicated with possibility and found himself compelled to

ask for her number, this beautiful woman walking along Carnaby

Street, carrying a miniature palm tree, safe in the knowledge that

he could whizz away again if she spurned him. She’d peered at

him, through the leaves of the palm, with a cool blankness as if this

happened all the time, strange man-boys on bikes being so forward,

and said that she wouldn’t give him her number but she would take

his. He’d assumed this was a deflection and so was surprised when

Daisy called the next day to ask him out. He’d said yes, and that

was that. There was no other correspondence in the days running

up to the date. In fact, they had both wondered if the other would

show up at all. But here they were now, in the late September sun,

together in one of the most exciting cities in the— and with no

drinks, he realises now. He stands up. White? Red? A bottle, yes?

She smiles, a broad grin he hasn’t seen before, and there’s a zip of

energy in his solar plexus, a tenderness in his lungs, and he walks

back down into the gloom again to order drinks, feeling oddly light.

*

On the other side of London, Adam Jiggins walks from Moorgate

station through the Barbican Centre – a large, imposing arts

venue – and towards his gym. Adam walks with purpose, or more

accurately, does his best to imitate a person who has a purposeful

walk. Until four months ago he would have hurried quite

naturally: power-walking from his flat in east London’s Hackney

to the small digital advertising agency in Farringdon where he

worked; jogging to buy lunch before all the good sandwiches were

taken, and running/sprinting/diving to catch the bus at the end

of the day. But now that he is unemployed (no, between jobs),

he has to remind himself to quicken his stride.

The gym is his salvation, an oasis in uncertain times. When

his agency began to lose clients, Adam considered joining a

cheaper gym – one without the fat white towels rolled up in

their cubbyholes, or the pretty blonde girls at the reception desk.

He knew he should be downsizing to save money in case – God

forbid – anything happened at work, but he had become too used

to certain standards, and anyway, it was false economy to join the

YMCA, with its questionable showers and rancid mats, because

he’d never go. This way Adam had justified shelling out the crazya-

month membership fee even after his bosses had called him into

the small meeting room/breakout space to explain ‘the situation’.

‘You’re f-firing me?’ he’d cried, his stammer always worse under

stress, taking a grip of one of the handles on the foosball table

beside him for support.

The Shape of Us 11

‘We have to make some bloody difficult decisions, and it’s

killing us. You must know that.’

Adam looked out of the window across to Smithfield Market,

where they’d once held public executions, feeling the proverbial

rope tighten around his own neck.

‘What if I went p-part-time? I could do three days a week

until…?’

‘We just don’t have the work in the pipeline. It’s this climate,

everyone in the industry is feeling the pinch.’

‘But we’re d-d-digital!’ he’d almost shouted, letting go of the

handle and causing three wooden footballers to spin on their axis.

It didn’t make sense. He’d watched a webinar on it only

the other week – digital marketing was the new rock and roll.

Companies were moving away from old-world advertising in

newspapers and on TV, and spending money on search engines

instead. Every movement was tracked, every click counted.

Adam had felt a surge of pride, knowing the online adverts

he created for pet insurance and wound glue were part of

the revolution. How could this be happening? And then it had

dawned on him – there was a revolution, yes, and advertisers

were spending more online, but only with the good agencies.

And to be honest, their agency was not very good. It wasn’t that

they were lazy – it was just that before you didn’t have to work

so hard to seem competent. You could sprinkle the conversation

with ‘social network’ this, and ‘augmented reality’ that, and walk

away with a six-figure contract. But now, every university grad

was a self-certified social media guru, the market was flooded.

And Adam had been washed away.

The memory gives him a stabbing pain in the sternum. He

tries to walk taller, puff up his chest. By now he’s worked his

way through the Barbican Centre and out the other side into the

setting sun, following the pavement that will spit him out near

the doorstep of his gym. He checks his watch, still on schedule.

After the shock of unemployment settled, Adam had felt briefly

liberated by all the spare time. He could go to the supermarket

and spend a whole afternoon browsing the foreign cheese section,

or head to a midnight screening of a cult film. Quickly, however,

the rush of freedom had faded, and he sensed something else

instead: ennui and a familiar depression. It was at the gym he felt

it most keenly. If he went at peak times he was acutely aware of

a countdown to nine o’clock or the end of lunchtime; a frenetic

energy he was no longer able to tap into. Mornings or afternoons

were the reverse – languid stretches of emptiness broken only by

the retired or infirm padding around the exercise equipment like

ghouls, or a damp grey mass, looming in the back of the steam

room like some silverbacked gorilla, grunting occasionally. Adam

had settled on late in the evening, long after the post-work rush,

imagining it made him appear hardworking and driven. He could

almost feel a wave of respect from the towel attendant when he

arrived close to ten o’clock. Though weekends were more oblique

time-wise, he had kept to his new gym routine and visited as late

as he could. Routines were good; all the therapists and self-help

books agreed on that. So here he was on a sunny Saturday evening

– shoulders back, eyes fixed on the middle distance, looking to

all the world like your average employed and employable Joe.

His foot gives way under him, causing him to wobble comically,

and Adam bends down to see what has made him slip. It’s a

corporate identity card in a plastic case belonging to one Mark J.

Smith. Adam knows the company, Mercer and Daggen, well – it’s

one of those big finance-y investment-y places a few streets over,

with its intimidating glass foyer and scowling security guards.

Carrying on his way, Adam inspects the photo more closely: Mark

J. Smith is an unexceptional-looking man in his mid-thirties, a

clone of a million other city workers – cropped brown hair, pink

shirt, slightly overweight and with sallow skin from too much

alcohol and time spent indoors. If you were playing Guess Who,

you’d be stymied – the only distinguishable feature is perhaps

that one earlobe seems slightly bigger than the other. Still, Adam

feels a pang of jealousy. Even though his old agency had been

too small to need such security, the pass feels like a talisman of

his past. It annoys him that he covets this pasty man’s job, a job

the man himself most likely resents. Sighing, Adam tucks the

security card into his wallet, reminding himself to return it to

Mercer and Daggen after his workout, and enters the gym to a

chorus of pretty blonde girls welcoming him in happy unison.

*